_____________________________________

Changes in Hungarian public law and the adoption of the Tavares Report have stirred up the debate surrounding Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU). The present piece of writing analyses whether the “nuclear bomb” metaphor can be applied to Article 7, by resorting to legal economics, criminal law theory and game theory; and represents these findings by focusing on a possible typology of international organisations and on the Hungarian Fundamental Law and its fifth amendment.

1. When two pedestrians cross the road

In Germany, the visitor can frequently observe that pedestrians stop at the red light even when there are no cars around. In Hungary our everyday experience differs, since we often find ourselves galloping across the street when the light is red. The situation is even more curious if we add that in Germany, the fine for irregular crossing is only 10 EUR while in Hungary this can amount up to 50,000 HUF (app. 165 EUR), which is almost twenty times higher. We can then ask ourselves, what is the reason for such a difference? Can cultural attitudes, the functioning of informal institutions or a stereotype of exactitude, which in this case results in a higher inclination to follow rules, supply sufficient explanation, or else should we attribute it to German parsimoniousness or the lavish lifestyle of Hungarian pedestrians?

The reasons behind this phenomenon might be less mysterious than we think, and they may also answer our questions regarding the understanding of the „nuclear bomb” metaphor applied to designate Article 7 TEU which has been discussed before on this blog. The present post supports the metaphor and wishes to illustrate its usefulness through the concrete example of the Hungarian Fundamental Law and its fifth amendment.

2. Old paradigm in a new context

The dilemma of choosing the appropriate incentives to prevent criminals from committing crimes has been around for long. If we continue our example above: why does one pedestrian cross the road while the light is still red and why does the other wait until the sign turns green? For a long time it was widely held that the prospective punishment deters potential criminals, who ponder upon the legal consequences of their actions. In the light of this statement, the more severe the punishment in prospect, the less likely they will risk taking an action. However, this inverse proportion of variables has never been substantiated by studies (that is why the reintroduction of the death penalty would bear no significant power of deterrence over life imprisonment, regardless of the fact that it would also be unconstitutional), because they have showed that an important variable was missing from the equation: that is the probability of the execution of the punishment (and thus the probability of the deterrent and theatrical Foucauldian spectacle). In the light of this reasoning, the so-called deterrence theory can be expressed with the help of the following formula:

A criminal will commit his crime as long as Uc > p * Up, where Uc is the expected utility [(u)tility] from the perpetration of the crime [(c)rime], p is the probability of successful investigation [(p)robability] and Up is the decrease in utility in accordance with the degree of the punishment [(p)unishment]. Consequently, if 10 out of 10 irregular crossings are duly punished by authorities, then even the most risk-loving pedestrian will reconsider his plans of crossing the street when the light is red, regardless of the degree of punishment. On the contrary, if the probability of the imposition of a fine is close to zero, then however high the amount of the fine may be, nobody will take it seriously, since as lex imperfecta, it will never bear an actual legal consequence.

While the above formula is evidently a simplified model to depict the mechanisms of criminal actions (for instance it does not take into account psychological factors, attitudes of risk-taking, and operates under the presumption that the perpetrator always acts rationally, which is not the case for example with crimes committed as a result of provocation), it can shed a new light on the international commitments of states. Of course there is again the presumption of rationality behind the application of formula to states as well, however, if we use it with the rational bureaucracy of state apparatuses in mind, this is a very plausible assumption.

3. We need a forum, but what kind of forum?

It is often reiterated that international law is nothing more than soft law. The question is whether this is true with regard to all kinds of international commitments (see for example the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights which unilaterally questions this assertion in relation to compliance with standards of the European Convention of Human Rights), and how this can be interpreted in relation to EU law. In all cases of compliance with international and EU law, there has to be a body of judicial nature which takes a position in cases of compliance with international commitments, because without such a body present, the right side of the deterrence formula would be undefinable and we would only be able to talk about unilateral commitments of states.

The right side of the formula is composed of two elements: the probability of holding the state accountable of its failure to comply with the commitments, and the prospective legal consequences. Naturally, if the arbiter which takes a position in cases of compliance or non-compliance is a judicial forum with concrete discretion, the probability of uncovering the infringements and imposing sanctions is higher than in a case when a political body is empowered only to adopt a political declaration or recommendation. There is a great institutional variety between these two extremes, for instance, the model can be further supplemented by the prestige of the international institution adopting a resolution only, which, similarly to an effect of a sanction, can potentially be detrimental to the reputation of the state in question, therefore it can have a stronger effect than the opinion of a not-so-reputed advisory body.

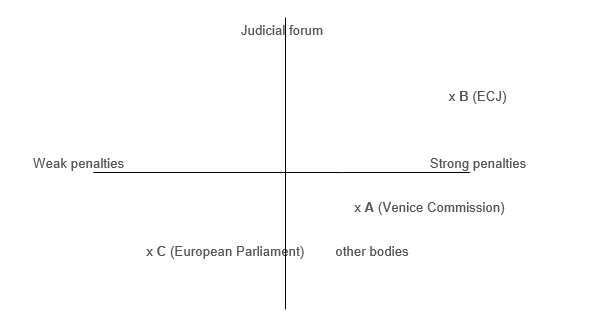

Consequently, international arbiters can be represented along two imaginary coordinates, one of which represents the nature of the institutions, while the other depicts the strength of the applicable sanctions:

To give an example: the Venice Commission can “only” issue opinions, however, by virtue of its expertise and prestige this apparently weak discretionary power can involve relatively important consequences (such as loss of prestige or the accusation of turning away from the rule of law), that is the reason it appears in the lower right corner of the figure. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) has strong competence regarding infringements and other similar procedures, thus it is placed in the upper half of the figure, where, for that matter, we could also place the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), as even though its decisions are of inter partes effect, they serve as minimal standards for constitutional courts in member states, which is also stated in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (Art. 53). The relative position of the ECJ and the ECHR could be however subject of debate, despite the representational nature of the figure, so I do not wish to take a position in this question.

4. Fundamental Law, Article 7

The functioning of the above depicted applied theory is perfectly manifest in the Hungarian Fundamental Law and its fifth modification. I will not detail the process of constitutional codification, however I would like to highlight the fact that after the fourth modification of the Fundamental Law, three international organizations reacted immediately: the Venice Commission, which issued an opinion on the new constitutional framework, and two other institutions which are in a comparable situation from the perspective of our topic – the European Commission and the European Parliament. The story that followed is well-known: the European Parliament accepted the so-called Tavares Report, and from the part of the European Commission, Commissioner Reding held a speech in which she outlined three areas in the Fundamental Law that were considered problematic from the EU law perspective. This was followed by the fifth modification of the Fundamental Law.

Unsurprisingly, after the fifth modification the sovereign constituent corrected all three problems raised by the European Commission. However, the content of the Tavares Report and the opinion of the Venice Commission were taken into consideration to a lesser extent. How is that possible? It is not my intention to provoke the domestic sovereignty-protecting discourse, but I still find it thought provoking that the text of the Fundamental Law was modified exactly and only at those points which were formerly criticised by the European Commission. Applying the above described deterrence theory seems to provide a plausible explanation. Although the Commission alone cannot impose sanctions on the Member States for their Treaty opposing behaviour, as “guardian of the Treaties” it is a Commission competence to investigate these issues and launch an infringement proceeding which might lead to severe one-sum sanctions proportionate to the GDP of the given country, or daily sanctions which incite modifications.

What can the European Parliament do in comparison? It can initiate the “nuclear bomb” procedure. The constituent might think that this is not a big deal, because we know from the cold war experience that nuclear bombs are not used by civilized and rational leaders. Article 7 has the same effect, so the p component of the above explained equation converges to zero.

Looking at the fifth modification of the Fundamental Law from this perspective, it seems obvious that the possible severe legal consequences had a deterrent (thus constitution modifying) effect. Moreover it also highlights that Article 7 is a political mechanism which is very unlikely to occur, thus it stays on a rhetorical level and has no consequences.

Coming back to our metaphor, there is one small difference between Article 7 and a nuclear bomb: Article 7 is avoided not because of its unforgivable consequences (in comparison, the consequences of the excessive deficit procedure are more severe), but because the procedure developed around it makes it inapplicable due to its political character. This feature is demonstrated by the fact that the European Court of Justice does not even have a right to give its opinion, while all Member States have to agree in sanctioning the Member State subject to the proceeding. This can remind us of a prisoners’ dilemma with multiple actors. Member States would have to cooperate in order to regulate their rule-breaker partner; however they can only do that with the danger of sacrificing their separately developed bilateral relations. So, only one Member State which choses to help the partner under scrutiny (in order to put it under obligation), would be enough to jeopardize the procedure. Obviously all Member States know how they can take advantage of such a situation, so foreseeing the dominant strategies of the others, it will not be a partner in imposing sanctions either. The only exception I can imagine in this scenario is a very severe violation of the law in one of the Member States, as Balázs Fekete suggests.

5. Chances of de-nuclearizing of Article 7

In the past years the need for a more effective, value-protecting mechanism has arisen within the European Union. However, this contains the difficulty that even if the ECJ was involved in the procedure, creating an objective measurement for the violation of EU fundamental values would still be difficult. There are still some areas and ideas which might offer a certain kind of way forward.

One of them is the new mechanism based on the “Copenhagen dilemma” raised by the Tavares Report, which would examine the endurance of the criteria required from the states at the time of their accession. From the perspective of the latecomers such a scrutiny could be welcome because as the Copenhagen criteria are relatively new, the old Member States would finally also have to go under scrutiny from this point of view. However, a dilemma might also arise regarding the fact that due to such a steering mechanism, the feeling of post-accession finality (rule of law fact-finding) would be taken over by a new, constant urge to comply (rule of law programme).

Another potential basis could be the EU Justice Scoreboard launched in 2012. This initiative, which was launched strictly based on internal market motives, examines the effectiveness of the judicial organization of each Member State, as it can have a huge effect on the economy and the development of the whole EU internal market. The question might arise, whether this scoreboard will remain relevant only to the common market in the future.

I see a long-term potential in EU enlargement and the Treaty modifications or a new charter coming along with it, which so far has always been coherent with the deepening of EU integration. There are several variations in this regard, such as a deeper mechanism shaped especially to the Eurozone members together with the creation of a second budget, which would motivate the outsiders to join the deeper integration.

Last but not least, I also consider further developing the notion of EU citizenship to be great a possibility in the future, which has evolved from the right of workers to free movement to an EU-level fundamental political right. I also see potential in the annual reports on fundamental rights and the mechanisms which could be built around them in the future.

To put it in a nutshell, the “de-nuclearization” idea has some foundations, however in my view the key lies in the procedural principles which create the basis of the mechanism and in the exclusion of political deals from it. It is also possible that the potential of such a rule as the one outlined in Article 7 lies in its rhetorical power, which only fulfils its meaning in the professional diplomatic layers.

The views expressed above belong to the author and do not in any way represent the views of the HAS Centre for Social Sciences.